Prolog

The original source of children’s literature is folklore in its most varied forms – folk songs, folk tales, riddles, counting rhymes, etc. Experience of centuries confirm that fairy-tales are irreplaceable for the mental growth of a child.

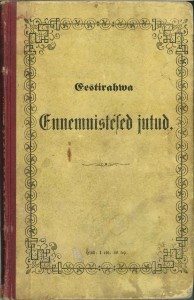

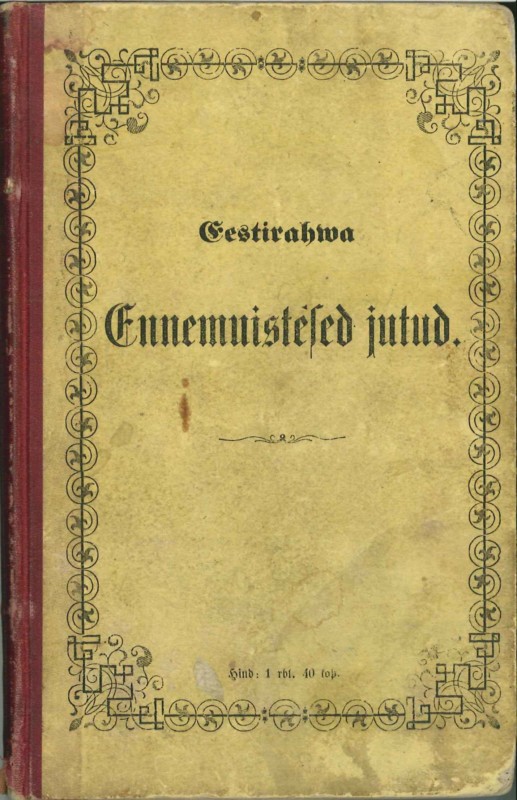

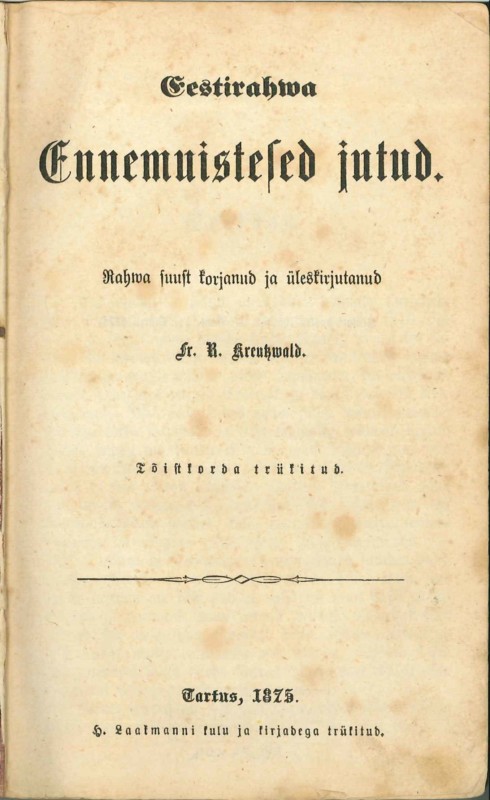

The first collections of fairy-tales were published in Europe in the 17th century (C. Perrault in 1697, etc.), and at the beginning of the 19th century the fairy-tales collected and reworked by the Grimm Brothers became well-known. Following their lead, F. R. Kreutzwald published Eestirahwa Ennemuistesed jutud (Estonian Folk Tales) (1866) which inspired also our other authors of the 19th century (J. Kõrv, J. Kunder) to publish their reworked fairy-tales. Literary fairy-tales (by H. C. Andersen, L. Carroll etc.) were born according to the model of folk tales, the tradition spread all over the world and has a honorary place among children’s literature even in our times.

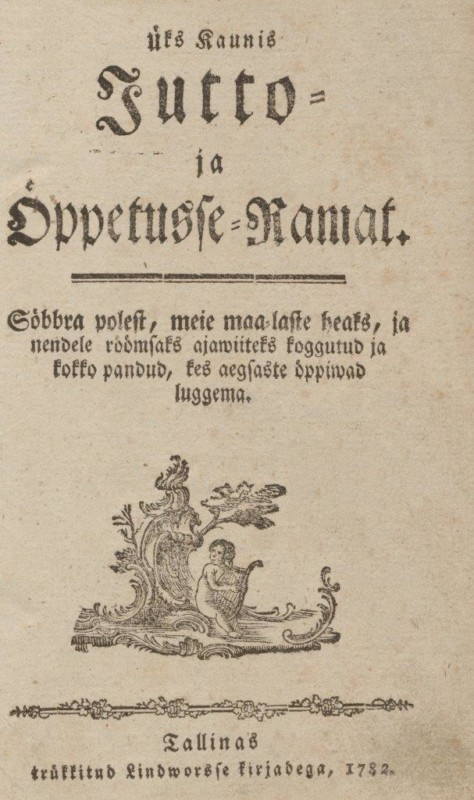

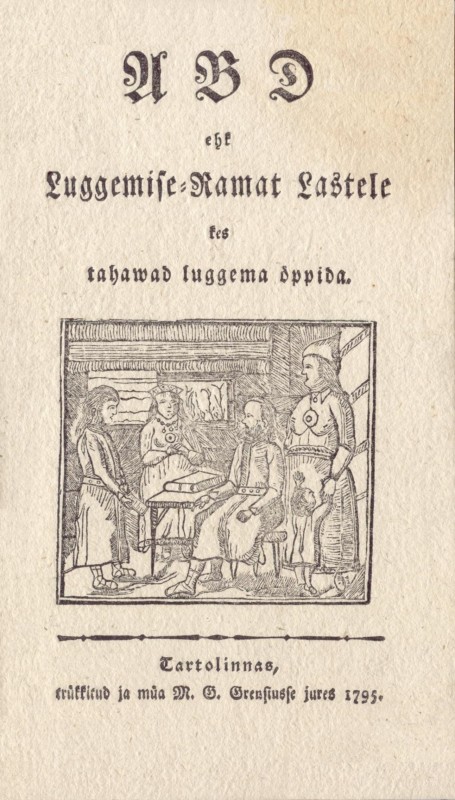

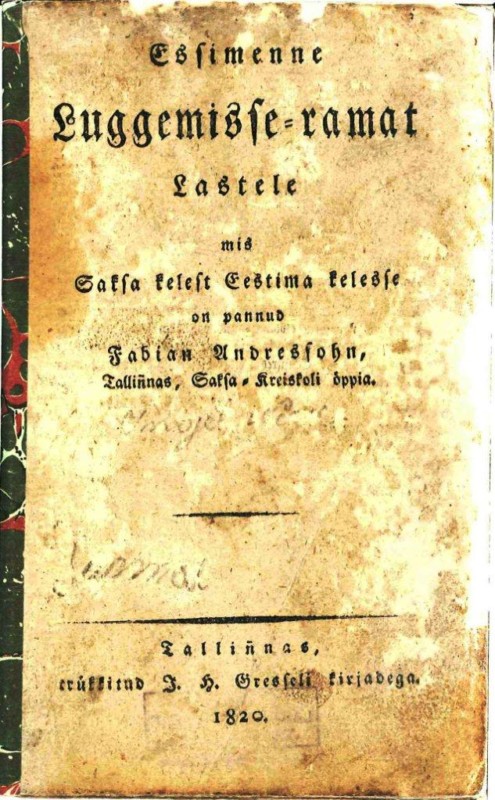

Alphabet books/readers have had great merits in the history of development of children’s literature. These and several other books in the national language enabled Estonians to achieve literacy rather early and to spread public education. Our first Alphabet Book was published already in 1641 as a result of the church reform of Martin Luther which required that the Word of God and studies at school should be in the local language. The oldest Alphabet Books that have survived until our times date from 1694 (in the North Estonian dialect) and 1698 (in the South Estonian dialect). Gradually, also texts with secular content began to appear in addition to religious reading. The first Alphabet Book with secular stories, ABD ehk Luggemise-Ramat Lastele (ABC or Reader for Children) by O. W. Masing, was published about a hundred years later (1795). Üks Kaunis Jutto- ja Õppetusse-Ramat (A Beautiful Book of Stories and Learning) by F. G. Arvelius (1782) paved the way both for children’s literature and science fiction. At the beginning of the 19th century only a little more than a half of the Estonian population could read but by the end of the century reading skills had become common.

Birth of Estonian children’s literature in the middle of the 19th century

The II half of the 19th century, known as the national awakening period, brought fresh winds to Estonia. The increased level of education and interest in reading among the population needed mental stimulation that could be obtained from reading materials in the mother tongue. Activisation was noticeable also in the field of children’s literature. Besides translations adapted to the Estonian reader also several original books with stories and poems were published.

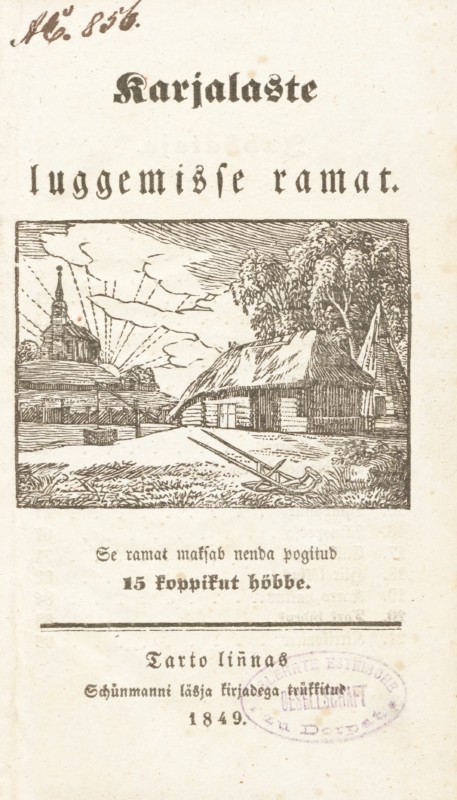

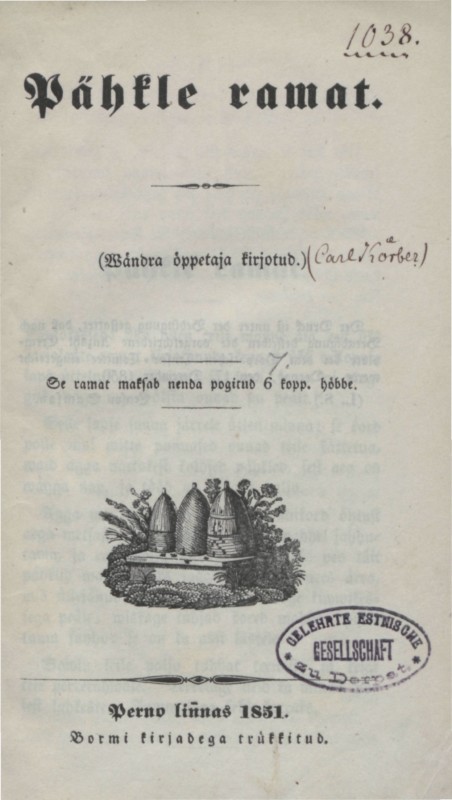

The German pastors, brothers Carl and Martin Körber made an appreciable contribution to the birth of Estonian children’s literature. Karjalaste luggemisse ramat (Reading Book for Shepherd Children) by C. Körber (1849) is the first reader specifically for children which was soon followed by the more artistic Pähkle ramat (Nut Book) (1851). The same author also wrote textbooks Koli-ramat (School Book) 1-3 (1854) and Uus ABD-Ramat (New ABC Book) (1872). Some of the numerous poems by M. Körber were also intended for children.

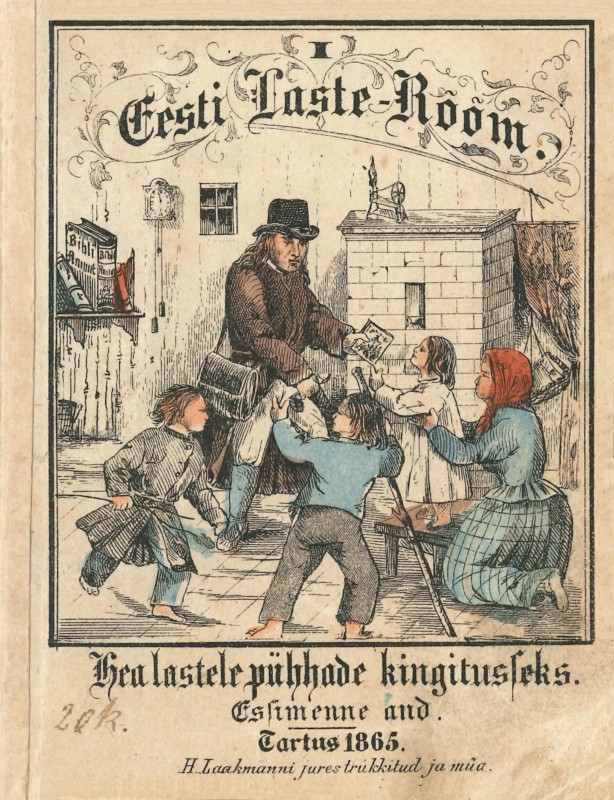

The first book of rhymes for children Eesti Laste Rõõm (Joy of Estonian Children) (1865) was created with by Johann Voldemar Jannsen, father of Lydia Koidula. The peculiarity of this book consists in the numerous pictures suitable to the content. Popular instructive verses have survived until our time.

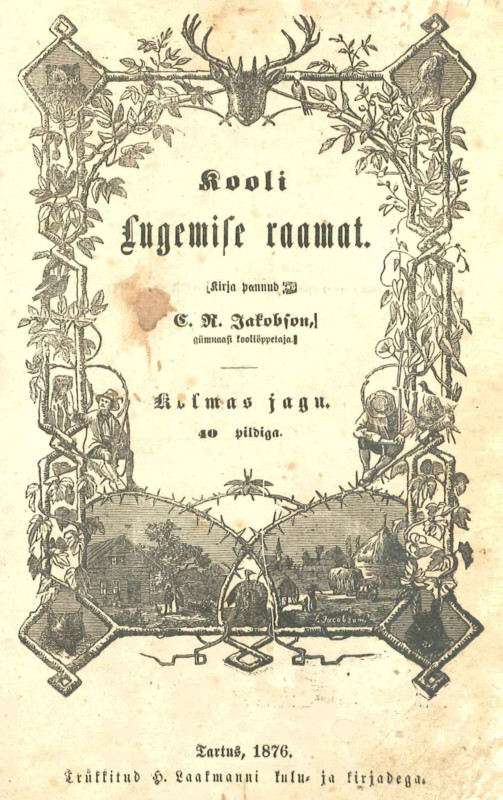

A number of school readers rich in content were published, the best known of which is Kooli Lugemise raamat (School Reader) I (1867) by Carl Robert Jakobson. Through readers also valuable literature began to spread among the people.

Estonian children’s literature during the last quarter of the 19th century

At the end of the century the Estonian readers could already become familiar with a larger choice of world literature which was partly also suitable for children (translations of the works of F. Cooper, A. Dumas, J. R. Kipling and others). Also the Estonian children’s literature took its first steps together with national literature. The first signs of criticism and theory of children’s literature could be found in the press.

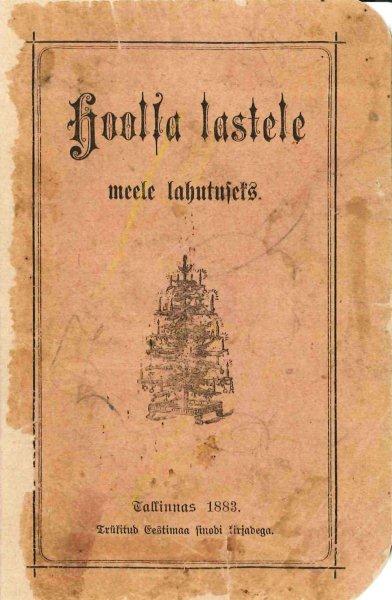

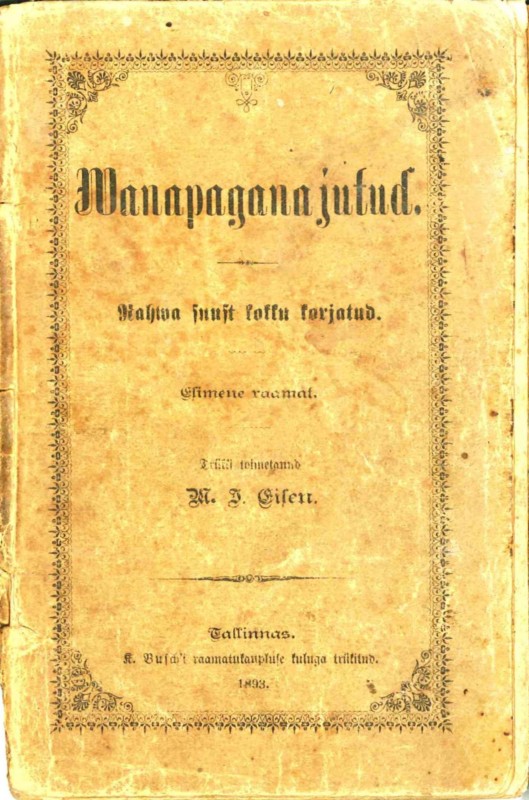

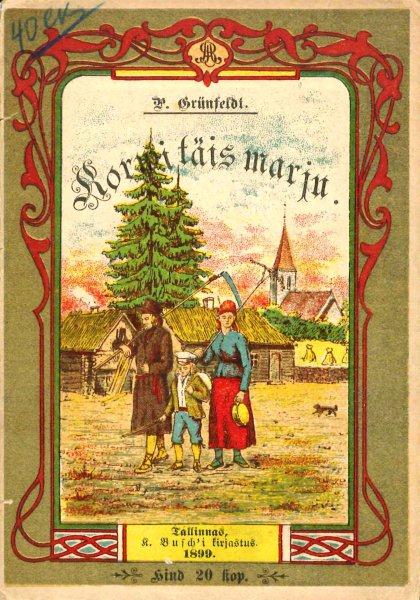

The amount of reading for children extended with the growth of book production. The period was characterised by different collections where original and translation texts of very varying standards could be found. Matthias Johann Eisen became well known by writing also several collections of folk tales in addition to the collection Laste varandus (Children’s Treasure) (1881). Jakob Pärn, the most productive story-writer at the end of the 19th century, was also an author of children’s books whose works are characterised by the black-and-white depiction method.

The literary heritage of Juhan Kunder to children is not so voluminous but all the more weighty. The author who is known also nowadays with his adaptions of fairy-tales was also the first one to adapt the epic Kalevipoeg to children (1885). His speech at the Estonian Society of Authors on the reading materials for Estonian children (on 3 January 1883) laid the theoretical basis for Estonian children’s literature.

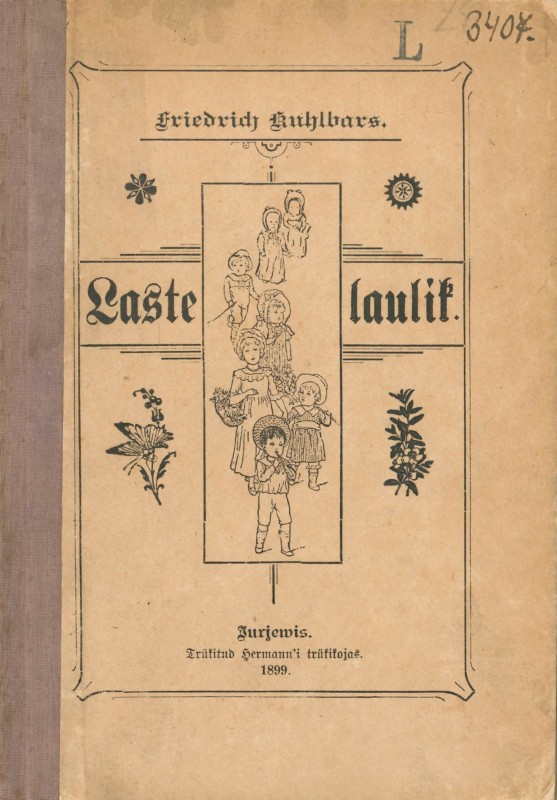

A considerable part of the secular songs of Estonian children at that time was related to Friedrich Kuhlbars. His Laulik kodus ja koolis (Songbook for Home and School) (1868) contained poems created to well-known melodies, some of which (“Teele, teele, kurekesed”, etc.) are sung even now. Ado Grenzstein’s (Piirikivi) “Viisk, põis ja õlekõrs” (1888) is equally well known. During the last quarter of the 19th century our national children’s literature for the first time gave a signal to the general public about its right to be close to the child, staying next to the child both in school and in everyday life.

Estonian children’s literature at the beginning of the 20th century

Despite the turn of the century, the children’s literature stepped along its way according to its actual possibilities. On the one hand, written texts intended for children were under the influence of the education theories and Christian morals of that time, but on the other hand, children’s literature was seen as an effective source of income. Thus a large number of publications appeared from which dual benefit was expected. More than 300 children’s books were published in 1900–1917 although only a few of them have remained in the history of children’s literature.

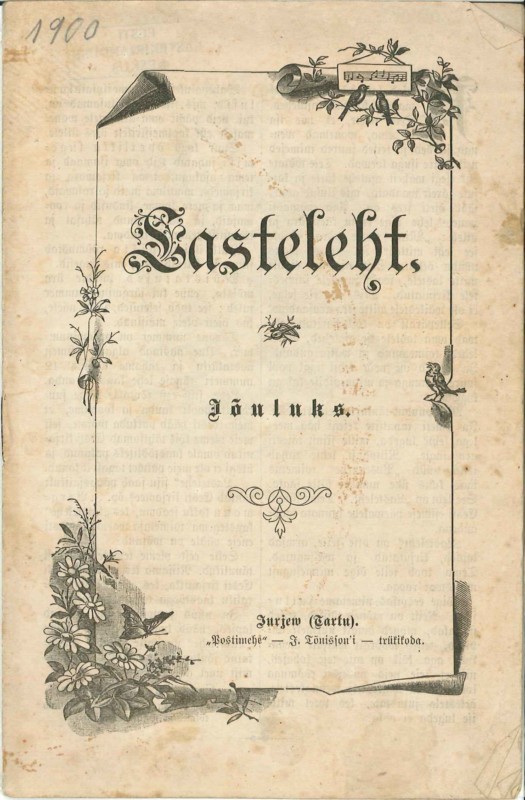

Periodicals have an important role in the development of Estonian children’s literature. In 1900 the first children’s magazine in Estonian, Lasteleht was born and during the following 40 years it published the works of almost all well-known Estonian authors. For instance, the first written work Siil by 15-year-old Friedebert Tuglas was published in the magazine in 1901. In 1900–1917 approximately 300 poems and 500 works of prose were published in Lasteleht, also numerous translations besides original works. There were several well-known artists among the illustrators of the magazine.

The Estonian Literary Society started to publish the series of books Nooresoo kirjavara (Literature for the Youth). In 1909–1916, 50 books rich in content were published – both translations and original classics. More sources of reading for children were published also in addition to the book series.

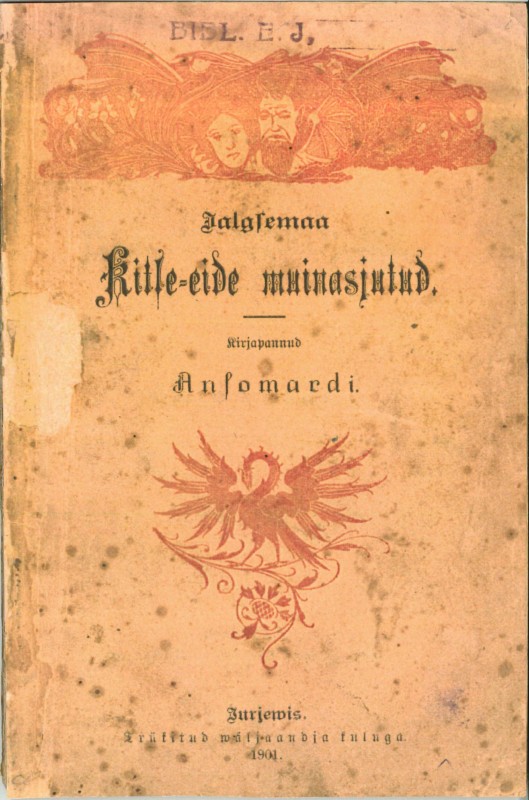

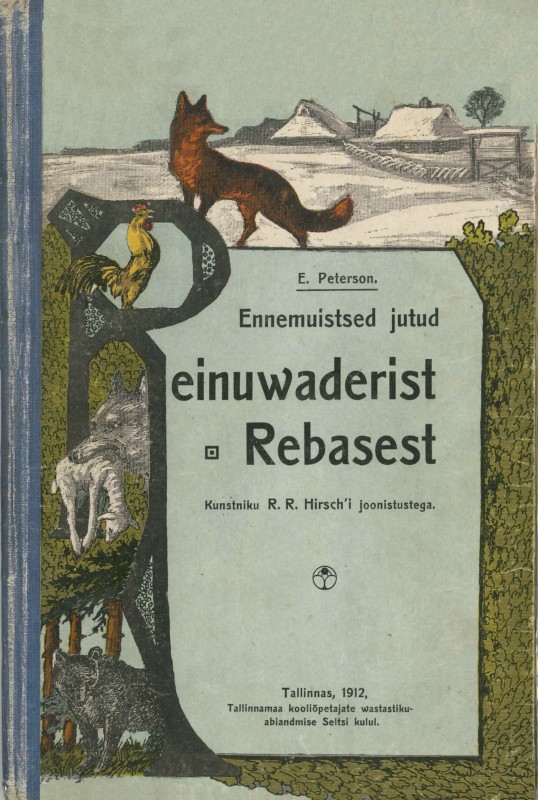

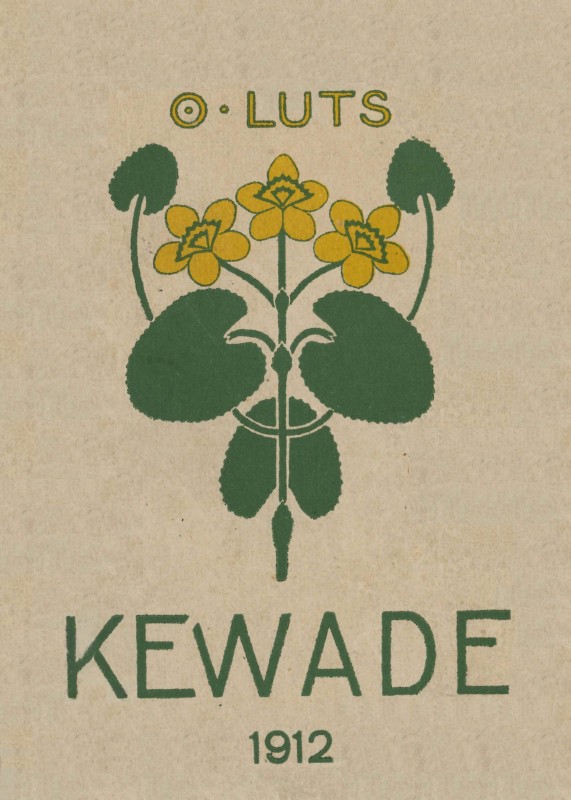

In retrospect, Kevade (Spring) I–II (1912-1913) by O. Luts which had not been originally intended for children took the most important place among storybooks of the beginning of the century. Also the collection of stories Meie noored (Our Youth) by Jaan Lattik (1907) was a success. Other authors of that time who wrote for children and are known also nowadays were Ernst Peterson-Särgava (Ennemuistsed jutud Reinuvader Rebasest (Old Tales about Reynard the Fox), 1911), Peäro August Pitka alias Ansomardi (Jalgsemaa Kitse-eide muinasjutud (Fairy-Tales of the Jalgsemaa Old Goat-Woman), 1901) and several others. Jaan Bergmann, Reinhold Kamsen, Karl Eduard Sööt and Ernst Enno wrote children’s rhymes. Funny and instructive illustrated stories in verses by Karl August Hindrey (Piripilli-Liisu (Crybaby) 1906, etc.) were very popular. Besides publishing children’s stories, August Kitzberg also took care of providing schoolchildren with a repertoire of plays appropriate for their age.

Children’s literature in the Republic of Estonia in 1918–1940

The independent Republic of Estonia opened up opportunities for national and cultural self-actualisation that had been oppressed by the Russification policy of the Czarist state. The children’s and youth literature considerably developed in the course of 1920–1930s both with respect to the volume and content. The number of children’s books increased almost 4-fold in comparison with the two first decades of the century. The best works of the children’s literature of the world became available to an Estonian child in his or her mother tongue.

In children’s prose the tales and stories were most common, followed by drama. Little of children’s poetry was published in books, the best poems were published in periodicals. Leading authors of children poetry were Ernst Enno and J. Oro.

Prose was characterised by varied subject matter, pursuit of suitable genres and demanding artistic attitude. Two main attitudes could be observed proceeding from the literary/educational views of the authors. One of them tried to create an ideal world where kindness always wins without fail. According to the other attitude, children’s literature was to proceed from real life and avoid making it more beautiful. Children’s literature also varied by gender and age of the readers. Publishing of literature for small children and youth, books for boys and girls began.

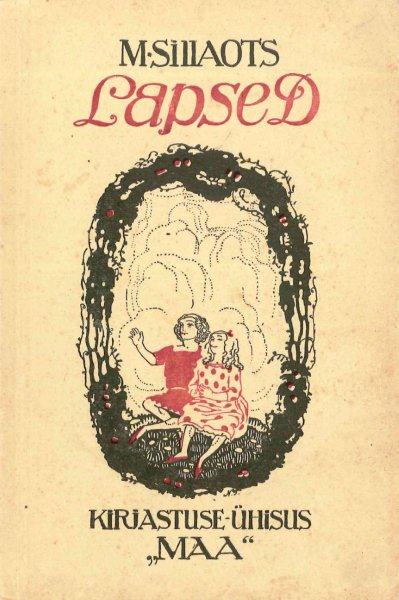

Children’s literature of the 1920–1930s mainly treats three subject areas – nature, history, and children’s life – with the special favourites being depiction of nature, particularly the animal kingdom in the form of realistic stories, fairy-tales and science fiction. Juhan Jaik, Karl August Hindrey, Richard Roht, Irma Truupõld, Marta Sillaots, Karl Ristikivi, Leida Tigane, E. Ramla (Elar Kuus) and many others became well known as children’s authors. Jüri Parijõgi, one of the initiators of the literature for boys, was outstandingly productive and his children’s stories are characterised by heartfelt depiction of a child’s daily life and skilful rendering of the inner monologues of a child.

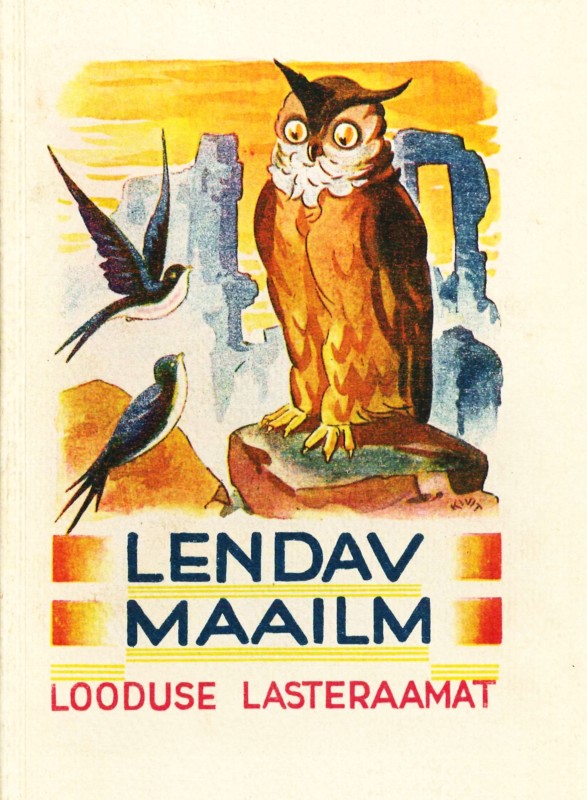

Loodus Publishing House became the main publisher of children’s literature in the 1930s and started to publish the very popular book series Looduse kuldraamat (Golden Book of Loodus), Kuldne Kodu (Golden Home) and Rõõmus Raamat (Joyful Book). Since 1935 the publishing house began to organise children’s literature contests where positive treatment of domestic matters was the main requirement.

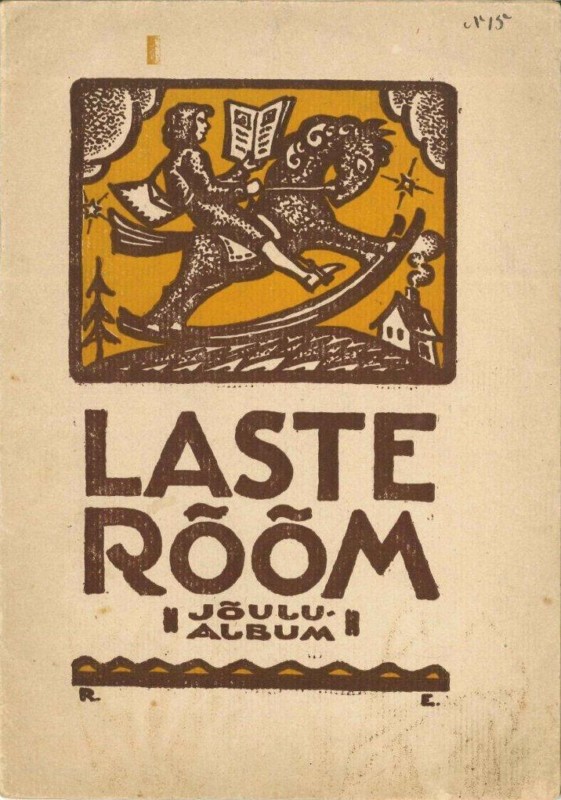

Publishing of children’s periodicals (magazines Laste Rõõm (Children’s Joy), Lasteleht (Children’s Paper), Vikerkaar (Rainbow), Laste Maailm (Children’s World), Laste Sõber (Children’s Friend), Väikeste Sõber (Friend of Little Ones), Õpilasleht (Student’s Paper) and many others) became more active.

While in the 1920s the children’s literature only acquired its definite place in national culture, in the 1930s the choice of subject matter already became extensive and it obtained a theoretical attitude and the attitude of art criticism. Numerous writings and reviews were published concerning children’s literature (by Jaan Roos, Jüri Parijõgi, Marta Sillaots and many others) and research into the history of children’s literature began. In 1933 the Youth Library (predecessor of the current Estonian Children’s Literature Centre) was opened at the Tallinn Central Library and was the first of its kind in Estonia.

War and occupations in 1940–1945

Unsettled times did not favour the development of children’s literature.

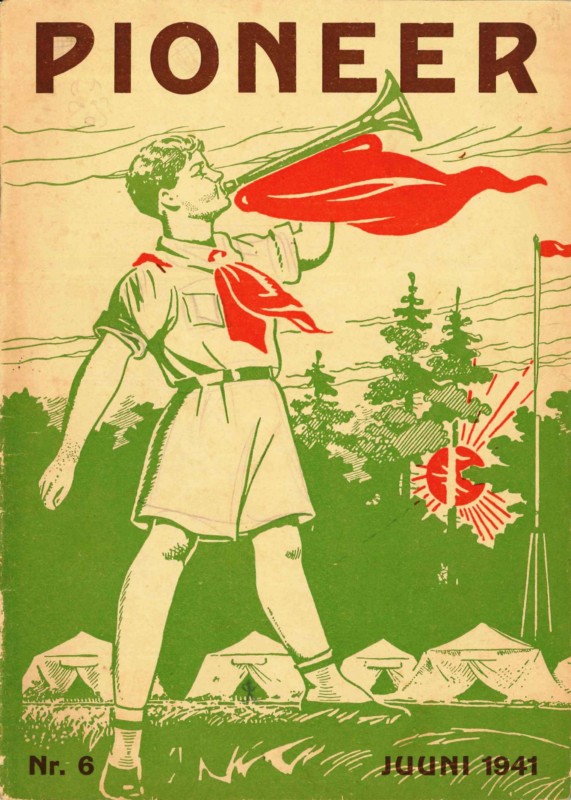

In the summer of 1940 a communist coup was performed and Estonia was incorporated into the Soviet Union. Active sovetisation and politisation began. Children’s literature was subjected to state control. The former children’s magazines were closed and two new magazines – Pioneer and Mäng ja töö (Play and Work) –were born to present the aims of the Soviet power. The state publishing houses recently created were able to publish a few children’s books, including Meelis by Enn Kippel (1941) which had been published earlier as a serial story Lembitu poeg (Son of Lembitu) in the magazine Lasteleht (Children’s Paper). The motif of the great historical friendship of the Estonian and Russian people was added to the text of the book.

The brief Soviet period was followed by German occupation. Living classics of the Estonian children’s literature Jüri Parijõgi and J. Oro lost their lives at the hands of communists in the turmoil of the change of power. In 1942–1944 only a few dozens of children’s books were published with Juhan Jaik, Kersti Merilaas, Marta Sillaots and many others as the authors.

Continuation of the Soviet occupation had a particularly grave effect on the destiny of children’s literature. A large number of creative people fled abroad in the autumn of 1944. An epoch of particularly intense red propaganda followed.

Estonian children’s literature under foreign power in 1945–1990

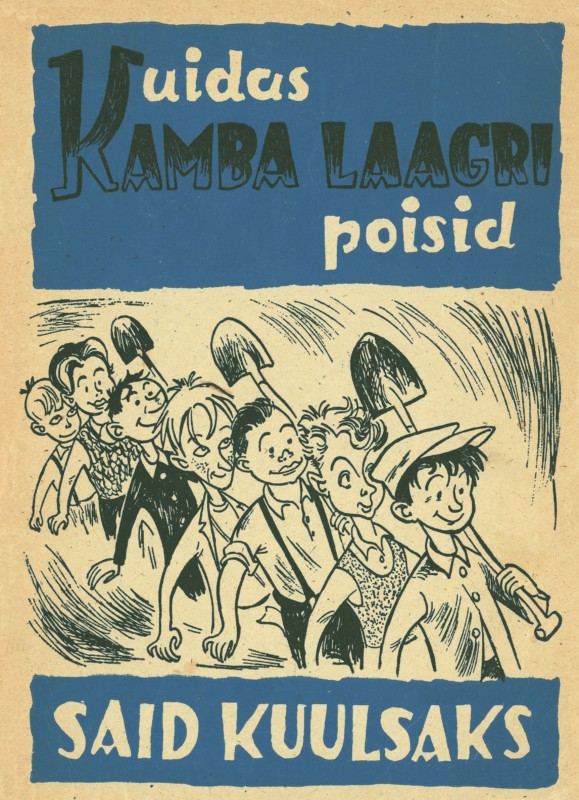

Children’s literature was under a lot of pressure during the Soviet occupation. The Communist Party regarded ideological education of the young generation as very important. Children’s and youth literature was to provide new role models and ideals and to depict enemies of socialism in as dark colours as possible. Apparent political obedience was mainly achieved with translated books which expressed outright ideology (e.g. Pavlik Morozov by V. Gubarev). The whole earlier children’s literature was harshly criticised.

Strict limits were imposed on children’s literature also from literary aspects. Realistic treatment of life remained almost the only possibility, with true life – or, rather, the idea of the communist ideology about true life – set as the main yardstick. Nature was the preferred subject matter (Richard Roht, Juhan Kallak) along with more recent and older history (Aadu Hint, Tõnis Braks). Leida and Aino Tigane, Kersti Merilaas, Elar Kuus and many other authors of the earlier period continued their work. Several new authors, such as Felix Kotta, Manivald Kesamaa and Ralf Parve, who was also the editor of the Pioneer magazine and of the Säde newspaper, became adjusted to the new situation. Children’s press helped very much to revive original children’s literature. Most of our children’s authors have come to literature through Pioneer (1940–1989) and Täheke (since 1960).

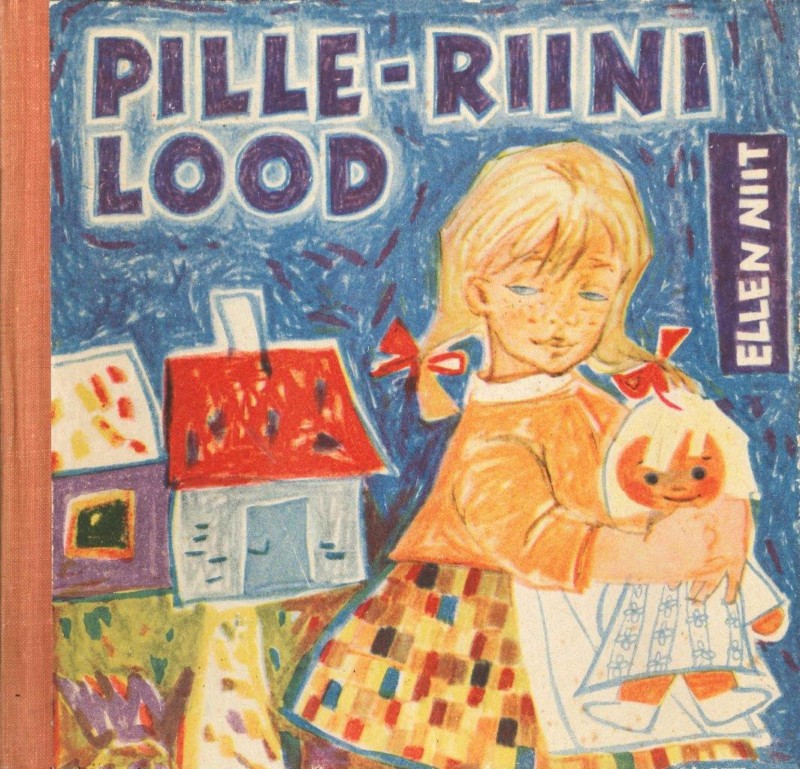

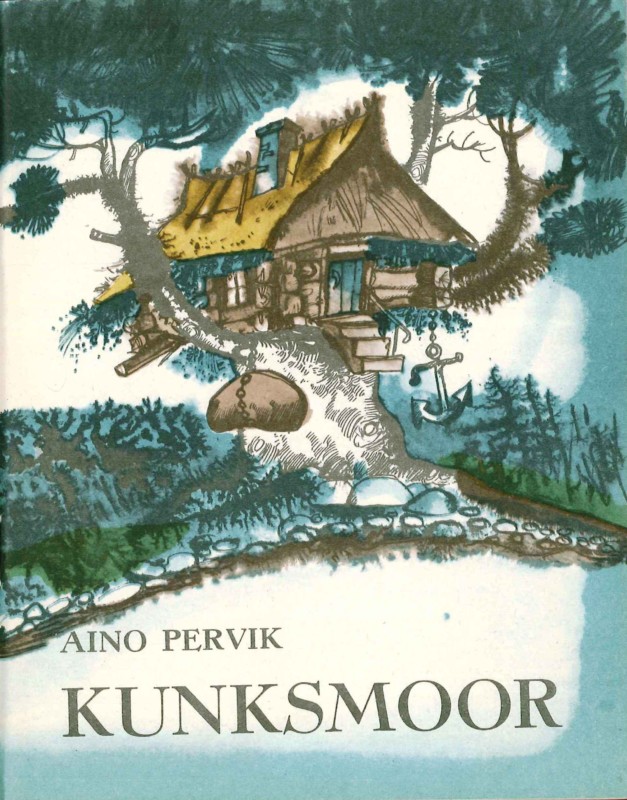

During the “thaw” after Stalin’s death also children’s literature was gradually released from rigid political pressure. A number of new authors started to write children’s literature during the second half of the 1950s and in the 1960s: Ellen Niit, Eno Raud, Heljo Mänd, Silvia Rannamaa, Aino Pervik, Holger Pukk, Silvia Truu, Villem Gross, Jaan Rannap, Heino Väli, Dagmar Normet, Aimée Beekman, Vladimir Beekman, Iko Maran, Venda Sõelsepp, Helju Rammo, Adolf Rammo, Kalju Kangur, Harri Jõgisalu, Boris Kabur, Uno Leies, Olivia Saar, Ira Lember and others. Leelo Tungal, Viivi Luik, Hando Runnel, Lehte Hainsalu, Tiia Toomet, Jaan Kaplinski, Asta Põldmäe started to write in the 1970s and Ott Arder, Astrid Reinla, Henno Käo in the 1980s.

Children’s poetry is characterised by increased mastering of the literary form and experiments with free verse and nonsense verses. The works of E. Niit became popular in the 1960s and in the following decades H. Runnel, V. Luik, O. Arder and others brought fresh breezes to children’s poetry Keywords of realistic children’s prose are a broader choice of subjects and honest treatment of phenomena in life (J. Rannap, H. Väli, S. Rannamaa, etc.).

Existence of literary phantasy was permitted again in the 1960s–1970s when there was more freedom in the political atmosphere. Possibilities of a literary fairy-tale were used also for the communication of hidden messages and social criticism (Mägra maja (Badger’s House) by Helvi Jürisson, Ajaprintsess (Time Princess) by Arvo Vallikivi and several others). Literary fairy-tales were written by Vladimir and Aimée Beekman, Robert Vaidlo, Aino Pervik, Dagmar Normet, Iko Maran, Henno Käo and many other authors. The Naksitrallid (The Three Jolly Fellows) series consisting of four books by Eno Raud (1972-1982) became popular also in other countries. Children’s playwrights were represented by Boris Kabur, U. Leies, H. Rammo, H. Mänd and others.

Nonfiction developed fast, with Heino Kiik, Rein Saluri, Viktor Masing, Jaak Sarapuu, Mall Johanson and others as the authors.

Print runs of children’s books were high (up to 100 thousand copies) and the prices low but also the number of titles was low. There were quite a few full time children’s authors in Estonia in the 1960s–1980s.

Estonian children’s literature in exile

In autumn 1944 the Soviet army occupied Estonia again. Experience from the earlier occupation made approximately 70 thousand Estonians leave their homeland, with also children’s authors among them.

The expatriate community very soon realised that the children’s book has an important role in maintaining the feeling of home and keeping up the language in the Estonian families. Reading materials in the mother tongue were published for children and schools already in the refugee camps. First aid in literature was at first organised through reprints. So the children could read Kalevipoeg (1946, 1949) and Eesti rahva ennemuistsed jutud (Estonian Folk Tales) (1949) by F. R. Kreutzwald. Also certain original works of great value were published, such as Raekooli õpilane (Student of Rae School) by Gert Helbemäe (1948). Contests of children’s and youth literature and several awards were initiated, and also expatriate press took care of providing children and youth with reading materials. The number of children’s books published in exile is not very high. Since 1960s also more neutral children’s literature from the Estonian homeland reached expatriate Estonian children.

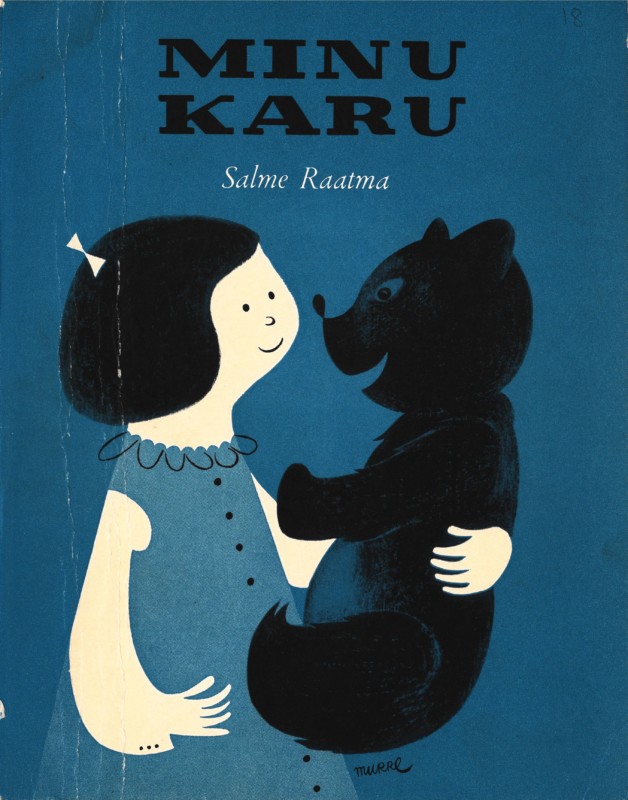

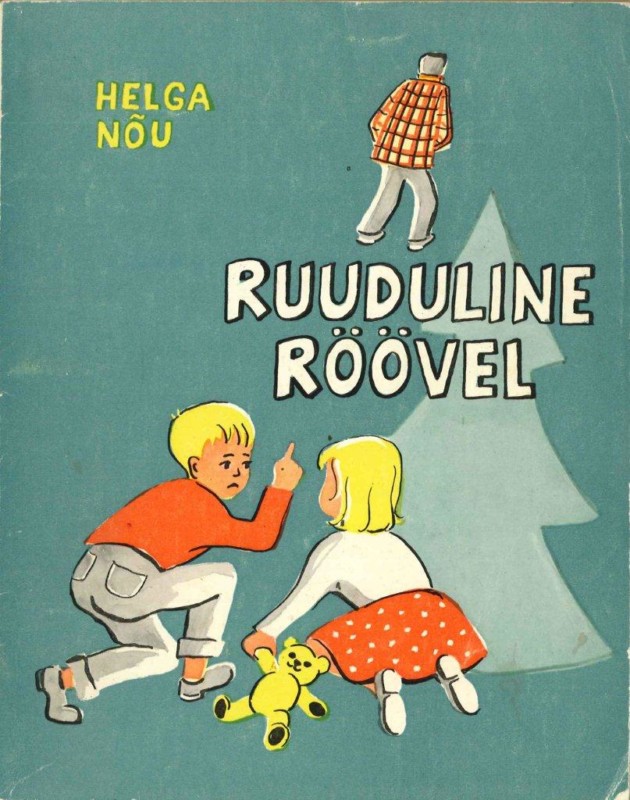

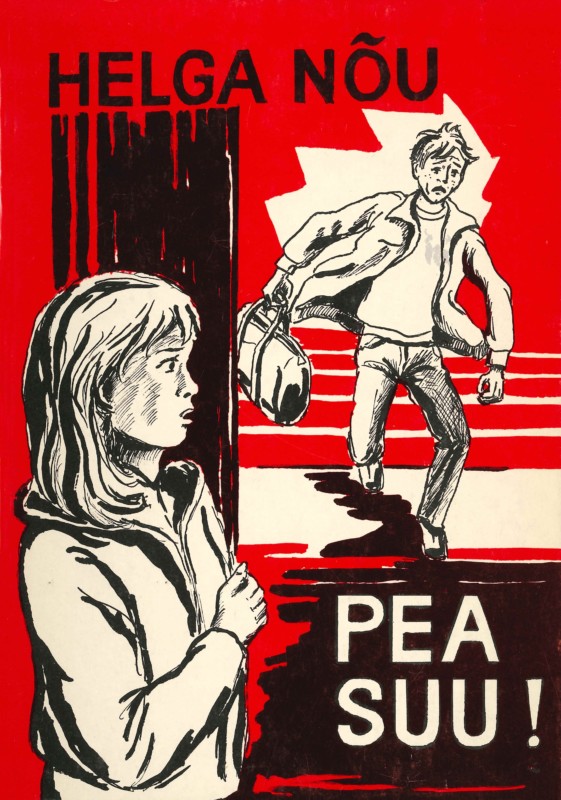

A few dozens of authors wrote for children in exile, some of whom had done it already before the war in Estonia (Helmi Mäelo, Pedro Krusten, Valev Uibopuu, etc) but some of them had started writing abroad (Helga Nõu, Salme Raatma, Magda Pihla, etc.). Prose became the predominant genre. The preferred subject matter was one way or another related to the far-away homeland but there are also some more recent works which treat the problems of children and young people today (Pea suu! (Shup Up) by H. Nõu).

Nowadays, children’s literature of expatriate Estonia has ceased to exist as an independent phenomenon. Reprints of a few children’s authors of the expatriate Estonian community (S. Raatma, H. Nõu) have been published in the homeland during the last two decades. More recent popular youth books by H. Nõu have already been published in Estonia after regaining of independence.

Children’s literature in Estonia after regaining of independence in 1991

Radical changes accompanied with the regaining of independence of Estonia brought about a crisis at first also in children’s literature. Only about ten original works were published in 1991. Later the situation improved. Many private publishing houses appeared which published at first only reprints and comic books. Children’s literature was gradually revived thanks to the activities of the Estonian Cultural Endowment and other supporting foundations. There are currently approximately 30 publishing houses and organisations which publish children’s books. The number of original children’s books is increasing fast – 26 original works were published in 2000 but in 2006 already 80. Children’s literature can be read also on the web.

The children’s literature of the 21st century is characterised by variety and flexibility in the determination of target groups (books for the whole family). Prose has still the leading role. Post-modern ambiguity, and combination of phantasy, science fiction, mysticism and the detective stories and adventurous styles are evident both in poetry and prose.

Authors of the older generation who continued their work were Aino Pervik, Heljo Mänd, Ira Lember, Henno Käo, Ott Arder, Leelo Tungal, Harri Jõgisalu, Lehte Hainsalu and many others. Children’s authors with dynamic debut were Edgar Valter (Pokuraamat (Poku Book) 1994) and Andrus Kivirähk (Kaelkirjak (Giraff) 1995). Authors of the younger generation who are writing prose for younger readers are Kristiina Kass, Kristel Salu, Kerttu Soans, Piret Raud, Heiki Vilep, Jaanus Vaiksoo, and new names have appeared also in children’s poetry (Ilmar Trull, Heiki Vilep, Wimberg, etc.). Development of the youth novel has been outstanding (Helga Nõu, Aidi Vallik, Katrin Reimus, Sass Henno, Diana Leesalu, etc.).

Täheke (since 1960) and Hea Laps (Good Child) (since 1994) are leading children’s magazines.

Krista Kumberg, Mare Müürsepp, Jaanika Palm, Ilona Martson, Jaak Urmet, etc. have discussed children’s literature in the press. In 1995 the monograph Eesti lastekirjandus (Estonian Children’s Literature) by Reet Krusten was published as the first thorough and systematic treatment of the history of our children’s literature.

Also the activities of the Estonian Children’s Literature Centre have received a lot of public attention. The Nukits Contest was initiated by the Centre (in 1992), the Nukits Almanac is published (since 1995) and contests of children’s and youth literature are organised in cooperation with the Tänapäev Publishing House. A working group on research into children’s literature is operating at the Centre and its main achievement until now has been Lastekirjanduse sõnastik (Glossary of Children’s Literature) (2006).